American Idle

I promised one final piece on TikTok, focused primarily on the network effects of creativity. And this is that, in part. But it discusses a bunch of other topics, some only tangentially related to TikTok.

All the points I wanted to cover seem hyperlinked in a sprawling loose tangle. This could easily have been several standalone posts. I've been stuck on how to structure it.

Some people find my posts too long. I’m sympathetic to the modern plague of shortened attention spans, but I also don’t want lazy readers. At the same time, this piece felt like it was missing a through line that would help pull a reader through.

And then I had a minor epiphany, or perhaps it was a moment of delusion. Either way, it provided an organizing conceit: I decided to write this piece in the style of the TikTok FYP feed. That is, a series of short bits, laid out vertically in a long scrolling feed.

This piece is long, but if you get bored in any one section, you can just scroll on the next one; they're separated by horizontal rules for easy visual scanning. You can also read them out of order. There are lots of cross-references, though, so if you skip some of the segments, others may not make complete sense. However, it’s ultimately not a big deal.

If I had more time, I might have built this essay as a series of full-screen cards that you could swipe from one to the next. Or perhaps tap from one to the next, like Robin Sloan’s tap essay (I wish there a way to export this piece into a form like that, if someone built that already let me know). And if I were even more ambitious, I would've used some Anki-like spaced repetition algorithm to randomize the order in which the following text chunks are presented to you, shuffling it each time a reader jumped in.The most meta way for me to ship this essay would have been as a series of TikTok videos. It would have been the Snowfall of TikTok essays. That would have also taken a year of my life (which, being locked inside because of a pandemic might be the time to attempt something like that?). Also, I am camera shy.

But as it is, this is what you get.

By network effects of creativity, I mean that every additional user on TikTok makes every other user more creative.

This exists in a weak form on every social network and on the internet at large. The connected age means we are exposed to so much from so many more people than at any point in human history. That can't help but compound creativity.

Various memes and trends pass around on networks like Instagram and Twitter. But there, you still have to create your own version of a meme from scratch, even if, on Twitter, it's as simple as copying and pasting.

But TikTok has a strong form of this type of network effect. They explicitly lower the barrier to the literal remixing of everyone else's content. In their app, they have a wealth of features that make it dead simple to grab any element from another TikTok and incorporate it into a new TikTok.

The barrier to entry in editing video is really high as anyone who has used a non-linear editor like Premiere or compositing software like After Effects can attest. TikTok abstracted a lot of formerly complex video editing processes into effects and filters that even an amateur can use.

Instagram launched one-click photo filters (after Hipstamatic, of course, though Hipstamatic lacked the feed which is like the spine of modern social apps), and later Instagram added additional features for editing Stories, and even some separate apps like Boomerang that were later re-incorporated back into Instagram as features.

Snapchat has a gazillion video filters, too, though many are what I think of as simple facial cosmetic FX.

YouTube has launched almost no creator tools of note ever. WTF.

TikTok launches seemingly a new video effect or filter every week. I regularly log in and see creators using some filter I've never heard of, and some of them are just flat out bonkers. What creators can accomplish with some of these filters I can't even fathom how I'd replicate in something like the Adobe Creative Suite.

TikTok’s Warp Scan filter is a bizarre concept for a filter in and of itself, but the myriad of ways TikTok users put it to use just shows what happens when you throw random tools to the masses and allow for emergent creativity. It only takes a handful of innovators to unleash a meme tsunami.

A longstanding economics debate is why we haven't seen the effects of the internet in our productivity figures. I won't rehash every side of every argument there.

But I know this: to take someone else's video and insert a reaction video of my own playing alongside it on the same screen is not easy in a traditional NLE. I'm not saying it's the moon landing, but it's not trivial.

On TikTok, you can just press the Duet button and start talking into your phone, and soon you have a side-by-side of the original video and your reaction video (you can choose from any number of their preset layouts for reactions). That's an explicit productivity boost; I can measure it in time saved for the same output.

You won't see that show up in GDP per capita figures, but it's real.

Remember 2 Girls, 1 Cup? If you've seen it, how could you not?

What interested me was less the video, which just horrified me, but the reaction videos of people watching it. Because 2 Girls, 1 Cup was a short video, I think it was a minute or two long, you could simply watch the face of someone watching the video and sync every reaction to every horrific beat of the video now forever haunting your memory, even though the original video wasn't visible on screen. The fun of the 2 Girls 1 Cup reaction video, but reaction videos in general, is that shared context.

Until TikTok came along, there wasn't an easy way to do reaction videos to other videos and have them make sense unless the original video had so much distribution that it was common knowledge. Or you could put the reaction video alongside or on top of or beneath the original video, but that required skill in using a non-linear video editor to lay those out and synchronize their timelines.

With TikTok's Duet feature, you can instantly record a side-by-side reaction video to anyone else's video. Duet is the quote tweet of TikTok. Or you don't have to do a reaction video at all. The Duet feature is designed simply to allow you to record a video that will play back alongside another video. It can be used for reaction videos, sure, but also to just provide a running commentary on other videos, and there are entire accounts built around both concepts.

But again, the Duet feature is built at such a low level that you can treat the feature as a primitive to replicate any number of other editing tools.

One such tool is to use the Duet feature as a dynamic matte. Since you know where your video will be placed in relation to the original poster's video, you can build a video mosaic.

Another is to use the Duet feature to, well, literally record duets.

But if you allow Duets to stack, well, eventually, one Wellerman can bring the whole chorus to your yard.

Someone truly ambitious could adjust the playback speed of various levels of Inception from the film Inception and stack them and synchronize them in TikTok using the Duet feature. If I had more time I'd do this myself, but the time has come for some time-rich kid out there to take this on.

Knowing that others can Duet your video means you can post any number of videos as prompts.

For example, you can read one side of the dialogue in a two-hander.

Knowing that TikTok has a Stitch feature, you can also post a question in a video and expect that some number of people will use Stitch an answer to your question and distribute that as a new video.

A popular prompt is "Tell me you're X without telling me you're X" or any number of its variants like "Show me you're X without showing me you're X."

Stitch wasn't necessarily designed to be used in this way, but as a primitive it's well-suited to any number of uses, including making TikTok a sort of video Quora.

Video prompts can come from not only other TikTok videos but commenters.

Some TikTok videos are made in response to requests posted in the comments. The comment is excerpted and published as an on screen text overlay at the beginning of the response video.

This is another of the nested feedback loops within the global feedback loop that is the FYP talent show. Once one example of this went viral, then the entire community adopted this as one of the norms of the community.

The Daily Show with Jon Stewart was a show almost entirely built around the reaction video. Stewart would play some clip of a politician being a hypocrite, or some Fox News anchor spouting their usual performative indignation, and then the camera would cut back to Stewart, his face frozen in some emoji mask of shock: eyes wide, mouth agape.

Social networks, and entertainment networks like TikTok, have completed the work of democratizing reactions. Yes, there's no reason you need to react to everything. But it's human nature. This is the social contract of the social media era. If you dare to shout your opinion or publish your work to the masses, the masses can choose to shout back.

Gossip litigates and fleshes out the boundaries of acceptable behavior within groups. Whereas gossip used to be contained, social networks now give it global distribution. This is one reason of many we've seen in-group and out-group boundaries drawn in bolder weight in this era. For every wide-eyed look of horror by Jon Stewart, you had the furrowed brow of disbelief that is Tucker Carlson's signature look, like someone in his elevator car passed gas.

Now extend that to clapbacks on the internet and you have a world in which back-channel gossip, a useful release valve and distribution channel for information about our peers, has become an open dialogue. The grapevine became the public feed, and every day, kangaroo court is in session.

TikTok's Duet feature belongs in the social media hall of fame of primitives alongside features like Follow and the Like button.

What feature better epitomizes the remix, react culture of the internet? Paul Ford once wrote that "Why Wasn't I Consulted?" is the fundamental question of the web. By then, social networks were well on their way to taking over from the web, and in the process, installing the plumbing by which the masses could finally directly opine to the masses, who could, in return, directly consult back. The "reply guy" is the consultant class of the internet, and mansplaining is its verb.

Yes, there are quote tweets and replies, but the TikTok Duet is the video analog, so simple and elegant in its design that you wonder why YouTube didn't launch it ten years ago, and then you remember that YouTube hasn't launched any creator tools of note since...ever.

What the Duet feature does, as described by how it would be done in a traditional non-linear editing program like Adobe Premiere, is the following:

- Copies the original file

- Inserts a new video track and a new audio track on top of the originals

- Allows you to lay down a new video on those new tracks

- Performs a whole series of steps to arrange the videos side-by-side on screen

TikTok abstracts a bunch of steps into a single function.

Yes, yes, some of these features in TikTok came from Musical.ly. But that's just a meta form of the theme of this piece! TikTok sampled from Musical.ly and improved upon it. They remixed a remix app.

But also, isn't this how innovation happens? We stand on the shoulder of giants and all that? Good artists copy, great artists steal?

TikTok enables, for video and audio, the type of combinatorial evolution that Brian Arthur describes as the underlying mechanism of the tech industry's innovation.

How many truly original ideas are there in Silicon Valley? Very few. Most have been tried umpteenth times in the past. Much of finding product-market fit in tech is context and timing. And people always underestimate the market side of product-market fit. When something fails, people tend to blame the product, but we should blame the market more often. The pull of the market is usually as important, if not more so, than the push from a product.

One day, the conditions are finally right, and an idea that has failed ten times before suddenly breaks out. Sometimes it's a tweak in execution, maybe it's an advance in complementary or enabling technology, sometimes it's a cultural shift.

Most of the best ideas in tech first appeared in science fiction books in the 1960s, and many of those are still waiting for their time to come. This is why rejecting companies that are trying something that's been tried before is so dangerous. It's lazy pattern-matching.

I do like Jeff Bezos' principle on when he decides to finally give up on an idea: "When the last smart person in the room gives up on the idea." But it also implies that you should bring some ideas back when a new smart person, or maybe a naive overconfident one, enters the room and champions the idea.

Given we know innovation compounds as more ideas from more people collide, it's stunning how many tech firms, even ones that ostensibly tout the value of openness, have launched services that do a better job of letting their users exchange ideas than any internal tool does for their own employees’ ideas.

How many employees join a firm and then spend a week in orientation learning where to get lunch, how to file expense reports, mundane trivialities like that. How many sessions are led by random trainers who don't even work at the company?

If you think of a company as an organism, and new employees as new brain cells, it's staggering how many join the company and begin from an absolute cold start. It's as if the company has chronic amnesia. What has the company learned from its past, what is its culture? When employees take months or even years to get up to speed at a company, companies should be embarrassed. Instead, it's treated as normal.

The free flow of ideas outside a company shouldn't, or in apps like TikTok, shouldn't exceed the rate at which knowledge flows inside a company, but I see it happen time and again.

The toughest job for any creative is the cold start. The blinking cursor on the blank page in a new document. Granted, writing a tweet, or even shooting an Instagram photo, isn't like composing the great American novel. But we tend to underrate the extent to which new users often churn without having ever posted anything to a social network because we only focus on those who do.

Now imagine trying to make a TikTok from scratch if you're older than, say, 19. The creative bar is high, you don't know how to dance, you're not up on the latest memes or popular music. Even if you're a teen, it's not easy to come up with a 0 to 1 TikTok.

But the beauty of TikTok's FYP algorithm and the Discover page is that you don't have to create a TikTok from scratch. The vast majority of TikToks are riffs on memes and trends that other users originate. It's no shame to be a 1 to n TikToker. Many on the platform achieve their first viral hit riffing on an existing meme.

Charli didn't invent the Renegade dance, Jalaiah Harmon did, but Charli made it famous. A lot of Charli and Addison's most popular TikToks are their interpretation of dances other people choreographed to songs other people composed.The ongoing debate on cultural appropriation seems to have no end in sight, but at least on TikTok there is a chance, with time stamps and some of the literal links the app creates between videos, to trace the origin of memes more easily.

Richard Dawkins introduced the term meme in his classic The Selfish Gene, defining it as a unit of information that spreads via imitation. He noted that memes evolve via natural selection just as in evolution. This memetic evolution happens via the same mechanisms as biological evolution, via variation, mutation, competition, and inheritance.

The internet writ large has always been fertile ground for the accelerated breeding of memes (cue toothless old prospector: "Back in my day sonny boy we had to spread memes via email chain letters"). But the TikTok app is perhaps the most evolved meme ecosystem to date.

Assisted evolution occurs when humans intervene to accelerate the pace of natural evolution.

TikTok is a form of assisted evolution in which humans and machine learning algorithms accelerate memetic evolution. The FYP algorithm is TikTok's version of selection pressure, but it's aided by the feedback of test audiences for new TikToks.

Memes can start from almost anything on TikTok. It can be the lyrics of a song, or just the vibe of a track, or both. A user can post a question or a challenge. In a single session on TikTok, you'll find videos of all types, most being riffs on existing memes (the variation).

Regardless of the provenance, any video, once loaded into TikTok, is subject to the assisted evolutionary forces in the app. Software tools like the Duet or Stitch feature and all of TikTok's other video editing tools assist in mutation and inheritance, and each remix of a source video becomes a source video for others to remix, generating further variation. Meanwhile, the competition on the FYP feed is fierce, and the survivors of that extreme selection pressure are memes of uncommon fitness.

In this assisted evolutionary ecosystem that is TikTok, and with an...umm...assist from the pandemic that kept hundreds of millions of people locked inside scrolling their phones, we've seen a marked contraction in the half-life of memes.

Memes used to dominate TikTok for what felt like weeks, and now it seems the memetic zeitgeist on TikTok shifts every few days, if not nightly. If I don't check back on TikTok every day, I find myself scrambling to catch up to the meta when I finally do open the app.

Of course, people grab TikToks and share them on YouTube or Twitter or as Reels on Instagram, but those apps receive flattened video files and can’t break them into component parts to be remixed the way you can on TikTok. Those other services are fine endpoints for distribution, but the creativity happens on TikTok. Don't get me started on apps like Triller (which feels like a Ponzi scheme).

People will litigate Instagram copying Snapchat's Stories feature until the end of time, but the fact is that format wasn't ever going to be some defensible moat. Ephemerality is a clever new dimension on which to vary social media, but it's easily copiable.

This is why TikTok's network effects of creativity matter. To clone TikTok, you can't just copy any single feature. It's

TikTok has a a series of flywheels that interconnect, and there isn't any single feature you can copy to recreate the ecosystem. Meanwhile, Reels has to try to compete while being one of like a half dozen things jammed into the Instagram app.

Markets in the internet and technology age are conducive to winner-take-all effects thanks to preferential attachment. This means that if you are first to stumble upon some flywheelMany like my friend Kevin use the term loops. I use flywheel merely to indicate I'm referring to positive feedback loops since loops can also be negative feedback. Also, I had to make that damn Amazon flywheel diagram for way too many presentations back in the day, it's mounted on a wall in my brain. in your business, the returns are even greater and accumulate more quickly than they would've in any other era in history.

Building a flywheel, though, often requires connecting a series of features at once. When I advise various companies, big and small, I often run into objections to my recommendations because of the popularity of agile or other incremental development philosophies. We end up at loggerheads on the V of MVP (minimum viable product), V having always been contextually determined.

If a flywheel requires three or four or even more things to connect in your app, it takes more work to ship all of them at once, and that feels like a riskier expenditure of your team's time. But, I'd counter: 1) often, testing a flywheel by definition means you have to build multiple features that work together 2) the returns of achieving a flywheel are often so high as to be worth the risk and 3) if you don't achieve any flywheels you are, as investor updates are so fond of saying, default dead.

Instagram famously has never had its version of resharing (e.g. retweeting). This reduced the velocity of photos and later videos on the service, a sort of brake on spam and misinformation and other possible such downsides.

But after using TikTok, it does feel odd to go through Instagram and not be able to grab anyone's photo to remix. Imagine you could grab someone's photo and apply your own filters, or grab just one element of the photo and use it in your photo.

Once we all live in the metaverse, this type of infinite replication and remixability will be something we take for granted, but even now, we're starting to see an early version of it on TikTok. This type of native remixability feels like it will be table stakes in future creative networks.

Fanfic is one text version of sampling and remixing. It doesn't require much more than your imagination.

It's always been really expensive, in both time and legal costs, to sample and remix film and television. TikTok has, with its short video format and tools, made remixing of premium video easier and safer. In Harry Potter TikTok, and its sub-genus Draco Malfoy TikTok, creators pull from the repository of the Harry Potter film universe as if it were on GitHub and merge themselves into branching storylines in which, well, creators become students at Hogwarts and catch the romantic interests of one Draco Malfoy.

The Discover page acts as the Fed in the central economy of memes on TikTok, while the FYP algorithm is the interest rate on meme distribution.

The Discover Page features hashtags. By the very act of featuring a hashtag, they signal to creators that if they create using that hashtag, they will get the distribution boost of that hashtag being featured on the Discover Page. Which raises the age-old conundrum, which came first, the Discover Page hashtag placement, or the hashtag's trending? The answer is yes. It's circular, an ouroboros of virality.

TikTok also posts the number of collective views on videos with that hashtag, helping creators gauge the potential distribution value of climbing aboard that trend.

TikTok is a mix of a centrally planned economy and a free market, much like many multiplayer video games where the game publisher manages the price and availability of various assets like weapons and armor while the players put them to use in the virtual economy.

The Discover Page is also where TikTok will feature corporate challenges. Yes, it's a paid placement, but the creative output is collective and distributed.

Because the most popular memes get super-distribution via the FYP algorithm, you can assume common knowledge of the meme among your viewers and just cut to the punchline. You don't need a bunch of what would be the video equivalent of exposition upfront. This keeps the majority of videos on TikTok compact, critical to the high cadence of the FYP feed. TikTok feels fast. Almost manic.

It also gives viewers that hit of in-group dopamine when they already know the references in your video.

If you don't understand a TikTok video and its references, you can trace the provenance from within the app in any number of ways. You can follow the hashtags in the caption or tap the sound icon and see all the other videos which have been made in that meme branch. Often that's enough to derive the context.

Or you can just read the comments. You'll find you usually aren't alone, someone will almost always have posted a comment like "In here before the smart people arrive" and then below that will be comments that explain the video to everyone else.

The internet, and the assumption of the internet, allowed for more complex and long linear narratives in television, shows like Lost and Game of Thrones. The assumption of Know Your Meme, or just knowledgeable commenters in the TikTok comments, allows for less expository and more compact, obscure TikToks. TikTok comments are a form of distributed annotation.

This technique of offloading the setup for a joke to the internet allows TikTok's, or even Tweets or Instagram posts to take on a form of what I call compressed narrative.

The old format of a joke, with a setup—A man walks into the doctor's office wearing only underwear made of Saran wrap—and then the punchline—and the doctor said "I can clearly see your nuts."—is dead. The internet killed the "joke."

Instead, the internet is mostly punchline, with the barest of setup, if any. It's on you to know the context. Go Google it.

And if you still don't get it, you weren't meant to.

An example is the "I ain't ever seen two pretty best friends" meme that went around on TikTok for a hot minute and has since just become a base trope of the TikTok creative universe. Videos started taking more and more circuitous routes to end with that punchline, throwing all sorts of sleight of hands before dropping it, out of nowhere, like an M. Night Shyamalan film twist.

If you hadn't heard of the meme or didn't know the reference, these videos would be complete mysteries. Even now, if you don't know what I'm talking about, this section will make no sense. Nor will comments like "We found the two pretty best friends" on various videos.

One of the better pieces I read last year was this on the death of political humor in the age of Trump. My favorite turn of phrase from the piece is that "Irony in politics, meanwhile, has reversed its polarity." David Foster Wallace predicted the death of irony, of cynicism, after an initial boom when the internet was coming of age. The lament of the humorist is that figures like Trump are beyond the reach of irony because they are already satires of themselves.I often lament when I refer to as fortune cookie Twitter, and to combat this, I think Twitter should set up a GPT-3 bot that constantly trains on each account, and the moment most of your followers can no longer distinguish between the GPT-3 spoof of your account and your actual account, you should be forced to vacate your account and allow the GPT-3 bot to replace you. You will have literally become a parody of yourself. Also, if for some reason I ever hacked my way into a famous person's account, my goal would not to be to request BTC or post something offensive. Instead, my goal would be to post a tweet that so resembles their voice that no one, not even the person who owned that account, could tell. They'd just think, wow, that's strange, I don't remember posting that, but it is something I'd post, so ¯_(ツ)_/¯

To me, humor has always depended on creating a gap and then helping your audience to hurdle it. In a traditional joke, the gap is the space between the setup and the punchline. When the audience's mind comprehends the joke, they soar across that gap, and the exhilaration is released as laughter. You don't want to carry them across, you want to do just enough to let them take that last leap themselves.

A comedian like Chris Rock will take something from real life and just point out the hidden social truth beneath it, and your mind gets that dopamine hit of acknowledging a social fiction that you'd otherwise observe without question. Like Moses, comedians part the sea of taboo and let you stroll through, laughing all the way at being able to get away with it.

Pre-cancellation Louis C.K. also lived in this space, exposing something of your nature that you were embarrassed to acknowledge. Either he'd absolve you of your shame by absorbing it all himself in a performance of self-loathing, or he'd just forgive you that fault by making it seem universal. Comedians let you look at yourself from outside yourself, creating a gap between you and your own nature.

Trump killed humor by closing that gap entirely, becoming such a parody of himself that shows like Veep seemed less dark satire than some form of fatuous cosplay even though they came first.

But humor is not so easily killed. You just need new ways to restore the comedic gap. Much of TikTok humor is oblique in form, making references that flatter you if you understand them and puzzle you if you don't. But for the latter, you then must set off on a journey to traverse that gap. And when you've completed that journey, you get the delayed satisfaction of getting the joke but also the pleasure of now being in the in-group.

But more sophisticated creators can also play with that expectation, setting off on what seems like a familiar meme, then subverting audience expectations.

Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, from the same parent company Bytedance, provides an interesting contrast in the styles of humor between China and America.

A lot of comedic videos in China use a laugh track sound effect. I can't remember the last time I heard a laugh track in a TikTok.

I want to draw some conclusion here, but I don't feel confident enough. Someone more familiar with the cultural differences in Chinese and American humor might clarify this for me.

Netflix brings international programs to the U.S. TikTok brings some Chinese programming to the States also.

TikToker @funcolle makes a sort of hyper-compressed episodic detective series that is filmed in China and spoken in Mandarin, but it works on U.S. TikTok thanks to onscreen subtitles. The sound she uses is, by now, as memorable to me as the theme song to any number of popular TV series like Game of Thrones.

If you can't solve these really short single TikTok video mysteries, you can turn to the comments section to get help from all the other viewers who've pored over the videos in detail and raced to post the solution.

One measure of a platform's power is the number of things people make with it that you had never been made before. Every week, I find videos on TikTok that I can't imagine having been made on any other app.

On TikTok, the comments have become creative terrain in their own right. Somewhere along the line, riffing on someone else's TikTok no longer required you to make a TikTok. Instead, you can just go into the comments and tack on a punchline to the punchline of the video and rack up hundreds of thousands of likes. Writing the most clever comment on a TikTok video has become its own art form.

I can't remember the last time I watched a good TikTok video without then opening up the comments to see what the peanut gallery came up with. Sometimes I read the comments before even finishing the video. TikTok's method of ranking comments almost always surfaces the best and most relevant comments to the top. However you feel about a video, it's uncanny how often one of the top five comments encapsulates it perfectly.

It's difficult in a video to feel the presence of other viewers in a tangible, meaningful way. The Twitch comment bar gives you a visible if somewhat bewildering waterfall of text as evidence of their presence, and the hearts on something like an Instagram Live or the bullet comments on Bilibili videos do the same.

TikTok comments, though, feel ike they extend the canvas of the video. Just as talent shows like The Voice require both contestants and voices to work, more and more it feels as if the TikTok experience is about watching the performers and then listening to the judges (all of us viewers) render their opinions via the comments. There isn't one Simon Cowell on TikTok, but in any comments section of any TikTok video, someone will play that role.

Never read the comments. Unless you're on TikTok, in which case, always read the comments.

Reading the comments on TikTok serves a communal function. It's like hearing the laughter of the crowd at a comedy show.

One of the existential challenges of life is truly connecting with other people's thoughts. Who can ever know that series of emotions and thoughts and dreams we call our consciousness? True human connection seems always out of grasp.

The pandemic exacerbates that sense of isolation. When most of our interactions are with flat faces on video screens, it feels either like we're living in a simulation or some solipsistic nightmare.

Before I check the comments on a TikTok I've just watched, I almost always have a strong reaction to that video. That's why opening the comments and finding that one of the first few comments perfectly encapsulates your reaction, then seeing it already has tens or hundreds of thousands of likes, is so comforting. This confirmation of a shared response creates, asynchronously, a passing score on a form of the Voight-Kampff test. It's a checksum on your humanity.

Many comments have begun using the inclusive second person singular, literally speaking for the rest of the viewers. These comments often begin with "POV:" as in "POV: You're lying bed at 2am scrolling TikTok." It's presumptive, and yet the best TikToks evoke such a consistent multiple-choice checklist of responses that it's rare the times I can think of an original comment that isn't already posted above the fold.

The sense of collective response in TikTok comments and the publicly visible view and like counts have been around long enough that users now assume enough others have encountered enough of the same memes despite everyone's FYP algorithm being tailored to their individual tastes. Many a comment on a viral TikTok will read like "Oh we're back here again."

Though I have said that TikTok isn't a social network—I don't know most people on the app, I don't have to follow anyone to have a good experience—the algorithm does create, through its efficient sorting, a sense of traveling through subcultural neighborhoods as you scroll down one TikTok at a time.

Users have adopted spatial or geographic language to describe this sense of shared viewing spaces. Various subcultures are described by appending -tok or TikTok behind a descriptor. Someone commenting on a particularly high-quality video might say "I've finally gotten Premium TikTok." People share weird niches they're on by saying things like "I'm deep into carpet cleaning tok" or "I don't know how but I've found music theory tok." Sometimes it's just one word, like "Sportstok or Liberaltok." Tok has almost come to be a suffix meaning "neighborhood" or "community," almost like Disney uses -land to describe themed areas in its parks like Frontierland or Tomorrowland.

Of course, we're all just in our FYP feeds, which just scrolls up endlessly, so it isn't an actual space. But we trust the visible view counts as evidence FYP is doing its job getting many of us with the same tastes in front of the same videos, and so this evidence of common knowledge creates a liminal third place that exists [waves hands at the air in front of me] out there.

I’ve tended to think of social networks as being built by people assembling a graph of people bottoms up, but perhaps I’ve been too narrow-minded. TikTok might not qualify by that definition, but it feels social, with FYP as village matchmaker.

There's been a lot written on Warner Media's decision to move some films from theatrical only windows to having a concurrent release on HBO Max. A lot of conclusions were drawn about theatrical's future based on Wonder Woman 84’s Christmas premiere in theaters and on HBO Max day-and-date. A lot of it is the usual knee jerk extrapolation that the internet is famous for, despite confounding circumstances like a pandemic, and despite Wonder Woman 84 being a single data point.

But one thing I'm confident of is that something is lost in not having the audible feedback of a hundred or more humans around you when you watch something, especially from genres that are built to elicit frequent emotional feedback, like comedies and horror films. At some point, perhaps we'll crack the nut on social viewing and how to make it more, umm, social, but for now, pre-VR metaverse, it's a shoddy facsimile of a crowd.

Look, I've streamed my share of concerts during this past year, and I don't miss standing for an hour between sets in a crowded club or bar, nursing a $9 beer in a plastic cup, waiting for my band of choice to get on stage.

And yet, I miss standing in that bar, my shoes sticking to the beer-soaked floor, trying to look at ease in my own skin while gawking at other humans.

In a year where we've been trapped inside for nearly a year now, there's something about the chaotic collectivist media art form that is TikTok that felt most joyful and genuine.

Thumbing through the FYP feed one portrait-oriented rectangle at a time felt like swiping from one bedroom window to the next on a tall skyscraper, peering into one user's bedroom after another (literally, as the bedroom is the most common space in which teens do their creative work). It's like a Chris Ware comic strip, with its architectural design, navigated one window pane at a time.

Because it's full screen, it can feel like my phone screen is literally a rectangular porthole. As if one user after another is hijacking my rear-facing camera and turning it into their rear or front-facing camera.

There's something about media like TikTok or ChatRoulette or Omegle, where so much of what you see is a creator directly addressing the camera, breaking the fourth wall from the start, that is immediately intimate.

One thing I wish TikTok would do is make it easier to trace multi-part videos from creators. Nothing drives me crazier than videos that end with "Stay tuned for Part 2" or "Like for Part 2" and then you spend like ten minutes browsing their profile trying to find the second part.

I understand that it's a sort of view count hack on the part of creators, but some videos do need to be broken up across installments. TikTok needs to add some sort of concept of a pointer or link to make it easier to jump directly to the next installment in a series. Perhaps it could be done via a playlist feature.

For now, the best way to trace linked videos is to visually scan the thumbnails on a person's profile and search for onscreen text reading "Part #" or just click on every video with the same visual grammar, the user in the same outfit in the same room with the same lighting.

(Since I wrote the note above, the app has added a way to highlight, on a creator's profile page, the video you just watched, and since videos are sorted reverse chronologically by creation date on the profile, often part II can be found next to the video you just watched, which is handy).

In another example of the community coming up with creative solutions, commenters on the first in a multi-part video series where the next part has yet to be published will now leave a comment saying that they'll promise to tag people who like their comment once the next installment is posted. In other words, users are serving as Mechanical Turk notification bots.

Another feature I wish TikTok would add is the ability to sort by descending popularity on any grid of videos, like on sound or profile pages. Please.

TikTok's needs to improve its search ranking algorithm. Trying to find popular TikTok's I remembered seeing back in the day was much harder than it should have been using TikTok's native search. A couple that I wanted to use I just couldn't locate, and even Google and YouTube didn't turn them up (a thing you realize after trying to do it more than once is how hard it is to create a comprehensible search query for certain TikTok's).

Network effects are powerful, but there are so many distinct types. It's important to understand exactly what type of network effect you have because they all scale and operate differently.

For example, Dunbar's number is just one form of limit on a very specific type of network effect. But there are dozens and dozens of network effects, all with their distinct quirks. Someone could make a lot of money just making a reference book of the taxonomy of network effect varietals in the world.

TikTok is an extreme experiment in not only making creative network effects endogenous to its app but to the medium of video. Like some video Minecraft, almost everything in the app is a replicable chunk of bits that you can combine into a larger configuration of bits, and the resulting creation becomes, itself, a chunk that anyone can take and splice or mutate or combine however they want.

This is anathema to old media, most of whom have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to lock up their content behind copyright law, DRM, and any number of other mechanisms meant to slow the rate of reproduction and iteration of their work. It has the effect of slowing the evolutionary feedback loops on all of that work.

TikTok's "OODA loop" is collective and distributed, and it spins thousands of times faster than that of big media.

When I first joined the Amazon Web Services team in 2003, it was still a small Jeff Bezos-sponsored project. There were only some 15 people or so on the team at the time under the leadership of now Amazon CEO Andy Jassy.

A book Jeff had us read, one which he said should serve as an inspiration for how we'd design AWS, was Creation: Life and How to Make It by Steve Grand. It's a book about programming artificial life, but the core principle that Jeff wanted us to take from it was the idea that complex things like life forms are built from very simple building blocks or primitives. It's the same thesis as that in Stephen Wolfram's A New Kind of Science.

The key implication for AWS from the book was about how to design the first AWS primitives. Jeff urged us to include only what was necessary and nothing more. If you were designing a storage service, like S3, you'd need functions like get, write, delete, but you wouldn't want to layer in things that weren't part of storage, like security. That should be a separate primitive.

The reason to design your primitives with the utmost elegance is to maximize combinatorial optionality.

This is one of the most elegant things about TikTok's design. It includes a ton of primitives, and they are almost all ones you can combine or link.

More than that, every element in a TikTok is a building block you can replicate and use in your own TikTok. The most important of these is the soundtrack or sound of your TikTok.

Be careful of taking this idea of building primitives too far. In many ways, choosing what level of abstraction to stake your ground on is one of the most important questions any company must answer.

The answer is contextual. Abstract at too high a level and someone can come in beneath you, with something like AWS. In some ways this is a form of disruption.

Build at too low a level, however, and often someone will abstract at a level above you and siphon all the value of that market above your product. Many of TikTok’s filters are abstractions of a lot of things, almost like Lightroom Presets. As many of us learned early in this pandemic, maybe paying a few bucks for a loaf of bread is preferable to having to spend hours of our free time mastering baking.

When I think about modern remix culture and apps like TikTok, I often think back to Mixel, an app designer Khoi Vinh launched years ago. It was an iPad collage app.

In his blog post introducing Mixel, Vinh wrote:

Because of the componentized nature of collage, we can add new social dimensions that aren’t currently possible in any other network, art-based or not. Mixel keeps track of every piece of every collage, regardless of who uses it or how it’s been cropped. That means, in a sense, that the image pieces within Mixel have a social life of their own. Anyone can borrow or re-use any other piece; you’re free to peruse all the collages (we call them “mixels”) and pick up literally any piece and use it in your own mixel. If you don’t like the crop, the full, unedited original is stored on the server, so you can open it back up in an instant and cut out just the parts you like. Mixel can even show you everywhere else a particular image has been used, so you can follow it throughout the network to see how other people have cropped it and combined it with other elements.

The thread view turns collaging into a visual conversation, where anyone can remix anyone else’s work.

Though Mixel is no longer around, what he describes presages modern meme culture and TikTok.

Inherent to digital culture is the remix.

In Mark Ronson's TED Talk on How Sampling Transformed Music, he says:

That's what the past 30 years of music has been. That's the major thread. See, 30 years ago, you had the first digital samplers, and they changed everything overnight. All of a sudden, artists could sample from anything and everything that came before them, from a snare drum from the Funky Meters, to a Ron Carter bassline, the theme to "The Price Is Right." Albums like De La Soul's "3 Feet High and Rising" and the Beastie Boys' "Paul's Boutique" looted from decades of recorded music to create these sonic, layered masterpieces that were basically the Sgt. Peppers of their day. And they weren't sampling these records because they were too lazy to write their own music. They weren't sampling these records to cash in on the familiarity of the original stuff. To be honest, it was all about sampling really obscure things, except for a few obvious exceptions like Vanilla Ice and "doo doo doo da da doo doo" that we know about. But the thing is, they were sampling those records because they heard something in that music that spoke to them that they instantly wanted to inject themselves into the narrative of that music. They heard it, they wanted to be a part of it, and all of a sudden they found themselves in possession of the technology to do so, not much unlike the way the Delta blues struck a chord with the Stones and the Beatles and Clapton, and they felt the need to co-opt that music for the tools of their day. You know, in music we take something that we love and we build on it.

One of the most revolutionary aspects of TikTok is how effortless it makes it to sample or interpolate any other TikTok video.

Anyone who's used a non-linear editor like Adobe Premiere, Final Cut Pro, or Avid Media Composer knows the standard multi-pane interface. And any editor knows that editing begins with importing all the media, the shots from dailies, the temp music, and so on, into your media bin. From there, you drag elements onto the timeline to compose the edit.

Much of the pain of creating memes is gathering all the components, like images, from the web. In the modern networked age, though, the media bin should really just be the entirety of the internet. Anything you want should just be a short search away. We're starting to get closer, though the library of material is still sparse, and many pieces, especially video, still require chasing down.

Someday, any sort of remix will just be a GPT-3 like interface away from composing. You'll just be able to write "This is Fine cartoon but the dog's face is Donald Trump" and it will just spit it out for you. If you're building this, please let me know, I'll write you a seed check.

The Verge interviewed a TikTok beatmaker named Ricky Desktop.

What makes a great TikTok beat?

You need concrete, sonic elements that dancers can visually engage with on a person-by-person basis. I know that sounds super scientific, but that is how I think about it. If you’re trying to make a viral beat, it’s got to correspond with the viral dance.

In order to lock in on that, you need elements of the music to hit. So for example, I have this beat called “The Dice Beat.” I added a flute sound, which in my head was like, “Okay, people will pretend to play the flute.” And then there’s the dice sound, where they’ll roll the dice. It was super calculated. I would create the music with the dance in mind.

I developed this little pattern. I pioneered the “triple woah” thing where in all the beats there’s three kicks — bum-bum-bum. So typically, when the bass drop hits, the dancers will do the woah (ed: an accentuated arm and elbow movement popular in TikTok dances) to emphasize the bass drop. Usually, the beat will keep going after that. But what I did, I would add three more bass hits, super calculated, so that dancers could do the woah three times or do three concrete dance accents.

The woah inspired Ricky Desktop to develop a score for the triple woah which then actually inspired dancers to choreograph and perform an actual triple woah.

Can you program human movement with music? It turns out you can. You use an API called TikTok. That's delightful.

TikTok beatmaker Ricky Desktop pictured, in his head, dancers performing some movement. Then he wrote a piece of music that included a musical cue intended to elicit that exact movement.

Then, later, some dancers on TikTok performed the movement he had pictured, exactly at the moment he had inserted the musical prompt. It's not just that he choreographed the human body via music, but how he did it. Ricky Desktop is a marionettist manipulating human bodies not via strings but music.

So I would post my beat and say, “Anyone trying to help me make this beat go viral?” Or I would say, “Who’s gonna create a dance to this new banger?” I’m giving an action item to whoever’s watching. And that’s important because it gives the person watching something to do.

The message is in the medium. That is, Ricky Desktop issues these to-dos inside of the video he uses to release his various sounds.

What makes a great TikTok beat?

You need concrete, sonic elements that dancers can visually engage with on a person-by-person basis. I know that sounds super scientific, but that is how I think about it. If you’re trying to make a viral beat, it’s got to correspond with the viral dance.

In order to lock in on that, you need elements of the music to hit. So for example, I have this beat called “The Dice Beat.” I added a flute sound, which in my head was like, “Okay, people will pretend to play the flute.” And then there’s the dice sound, where they’ll roll the dice. It was super calculated. I would create the music with the dance in mind.

In filmmaking, when you want a score for your film, you bring the latest cut of your film to a composer's studio, and they start riffing based on what they see on screen, incorporating some of the themes you're trying to evoke in that scene.

What Ricky Desktop talks about above is a different process in which he scores to visuals that only exist in his imagination, generic dance tropes like "pretend to play the flute".

This is a form of "inverted scoring." Or, if you prefer to go from the other direction, what TikTok dancers do with sounds is "visualizing."

The program WinAmp used to do software visualizations of music. TikTok is like Mechanical Turk for visualizing music.

If you've watched any amount of TikTok, you've doubtless seen someone answering questions by dancing and pointing to floating text overlays.

Now, they could easily just speak the questions and answer them verbally. There's no reason to have to dance to music while answering the questions.

To which I say, no one knows what it means, but it's provocative, it gets the people going!

This is one of many TikTok survey or poll formats, all devised by the users. On one hand, there are simpler ways to share this information. On the other hand, this is much more entertaining than a Twitter poll.

On the other hand, maybe all this choreographed dancing is something more of us should be doing to make our messages land. A teacher went viral on TikTok this year for filming herself trying to teach her class remotely over Zoom. Seeing her precise and broad gestures paired with her sharply articulated speech, you couldn't help but feel empathy for what a burden we've placed on our teachers, trying to make remote classes engaging over Zoom.

But perhaps we just lose some of our childlike exuberance and joy expressiveness as we age? Perhaps if we were more animated in our delivery, more people would remember what we said.

One of the most common weaknesses among managers and leaders is the illusion of transparency, though it is a problem for most people. It is the tendency to overestimate how much people know what you're thinking. It can ruin marriages or relationships, and it leads to a healthy market for therapy.

Young children have the a strong form of this illusion which is why in early childhood they are so frustrated when you don't understand why they're upset (and parents are likewise just as exasperated that their children can't verbalize why they're freaking out). Until later in life, children think you should know exactly what they're feeling, and it takes a bit of coaxing to tease out their inner emotional state. Ironically, despite their illusion of transparency, kids tend to be much more emotionally transparent and thus expressive.

It's when they finally realize that no one can see into their heads that they learn to lie. It's then that you wish they still had the illusion of transparency. When they become teenagers, the battle over transparency into their lives becomes literal: parents yell at their teenagers to keep their bedroom doors open, and those same doors slam shut after heated arguments. Their bedrooms become, like their thoughts, spaces they wish to protect from prying eyes.

This is all a roundabout way to say that a CEO communicating a company's top goal for the coming year in a TikTok dance, pointing to on-screen captions, isn't the worst idea in the world? Maybe this is the new Amazon 6-page memo.

Study any high-level memory competitor and they'll all say the same thing. Humans' visual memories are far superior to their memories for abstractions. It's one of the core lessons from the great book Moonwalking with Einstein. It's the reason people who have to try to memorize a thousand digits of pi or the order of a deck of cards turn numbers and letters into images which they place spatially in memory palaces.

In its heyday, which coincided with my childhood, MTV was dominated by music videos, and each of those was essentially a visualization of a musical track. To this day, I can't hear a song like A-Ha's "Take on Me" without picturing its music video. I haven't seen it in decades, but its cartoon sketches come to life are forever how I "see" the song. Likewise, I can't hear Michael Jackson's Thriller without conjuring its epic music video of nearly 14 minutes.

It doesn't even have to be a music video. A song incorporated in a film can permanently bond with the moving images on the screen. For example, I can't hear three tracks, one each by Huey Lewis, Genesis, and Whitney Houston, respectively, without picturing Christian Bale and quoting Patrick Bateman, and then being filled with a sense of self-loathing for having been indicted as someone who turns to the appreciation of cultural artifacts as a substitute for personality. If I mention Celine Dion's song "My Heart Will Go On," what do you see in your mind's eye?

TikTok is the modern MTV because (1) it increases consumption of music tracks that go viral on its platform as sounds and (2) any number of songs will forever summon the accompanying meme and visual choreography from my memory.

When Charli and other TikTokers formed the Hype House in Los Angeles, they were experimenting with IRL creative network effects. They created what was efffectively a commune to produce the D'Amelio TikTok Universe with Charli at the center as, I don't know, Tony Stark or something.

They started guest-starring in each other's TikTok's, some of them started dating and hooking up, and soon, to follow the entire extended narrative, you had to follow each other's accounts. Studios have tried to push out fictional versions of such networked series, but Charli et al just created it bottoms up, with TikTok as the distributor.

The Kardashian-Jenner clan are the clear predecessors who ran this type of crossover mindshare grab, but they're family. This new generation of influencers often aren't related, their common bond is just that they're young and famous in the age of social media and so they already all live together in a virtual universe held together by the gravity of popularity.

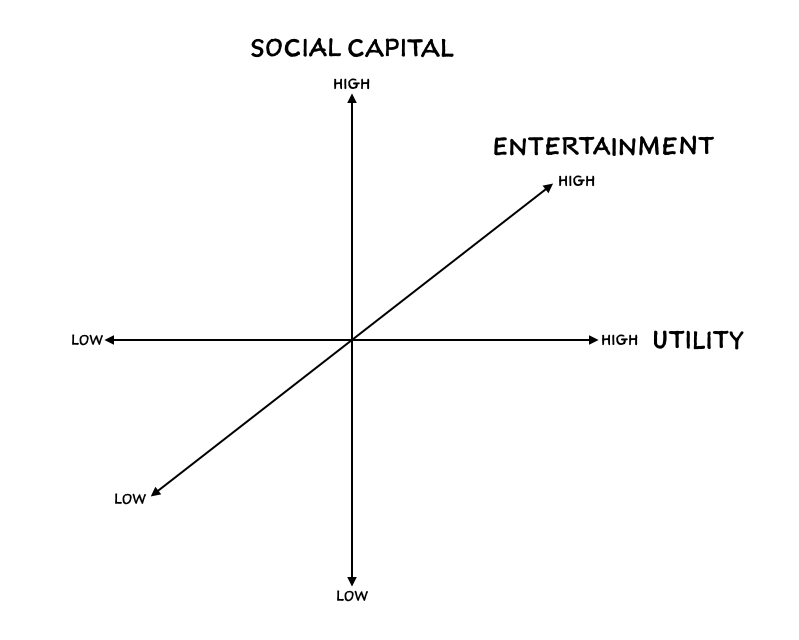

In Status as a Service, I wrote about how social networks require some proof of work to gain status.

A lot of TikTok's have the caption "I spent way too long on this" as a sort of plea for likes, but that wouldn't land if the proof of work wasn't visible on the screen. It is, and even non-creators can see it. Some TikToks seem like they took days to produce.

Have you tried using the in-app TikTok video editor? In some ways, it's loaded with really first-rate filters and effects, but in many ways, its user interface is inscrutable. I went to editing school and have used a variety of non-linear editors (NLEs) like FCP, Premiere, and Avid to edit video in a previous life, and I still tear my hair out trying to use TikTok's native editor.

The easiest videos to make are just ones where you film yourself live and apply a filter, but if you want to bring in pre-recorded video and mix them with other graphical elements, like text boxes, it is very painful to assemble them properly. My kingdom for a persistent timeline with a scrubber in the TikTok editor.

In one sense, it's staggering to ponder how many more videos TikTok would have if its video editor were more usable. On the other hand, every video that does make it onto the app feels like a miracle. The proof of work is in the pain.

If you're a movie star like Will Smith and you get a VFX studio to produce some whiz-bang TikTok for you, it will feel off, like driving a Ferrari down the street in Omaha. Authenticity or at least the sheen of one's own sweat equity is part of the TikTok aesthetic, and the canonical backdrop for any TikTok video is always some teenager's somewhat messy bedroom, just as it was in the heyday of the YouTube vlog.

On Instagram, you can get away with proof of wealth, but the TikTok aesthetic is proof of creative labor. The verdict is a bit more mixed on proof of hotness, though. I still think Instagram is a more welcoming home for pure thirst trap content than TikTok, where, if you want to honeytrap the simps, you're going to have to dance for it.

Something about a feed that can hit you with such a variety of styles and moods in such quick succession makes TikTok feel like the most modern of media channels. One second you're watching a dog communicate with their owner using a language mat, the next second some high school girl is roasting one of her classmates, the next you see a teen making an earnest confessional deprecating their own looks (only to have thousands of commenters offering affirmation), and then you might see a boat chase that you later realize is some drug cartel member filming a TikTok as police boats give chase (even Narcos be chasing them likes). At times it feels as if the FYP feed is a pastiche generator.

It is equal parts ironic and earnest, having long since surpassed its label as the cringey social network.

Whereas Instagram is performative, TikTok is performative and self-aware. It’s not that any single creator is self-aware, but that the Greek chorus in the comments will descend on anyone with the slightest bit of hubris like a pack of harpies.

In this rectangular proscenium that is TikTok, the fickle god of Zeus is played, of course, by the FYP algorithm. Everyone offers up their sacrifices of time and labor in the hopes of being graced by its favor, but its whims remain just capricious enough to keep everyone grinding.

If your FYP feed is dialed in to your tastes, you start to pre-react to videos purely based on the like count visible on the right hand side of the screen.

If a video has a high like count, even if it starts slowly I'll tend to give it the benefit of the doubt and stick around to the end, simply because this statistic has proved, in my experience, reliable evidence of a worthwhile payoff. The larger the figure, the more I anticipate a strong punchline or close. I'm like Tom Cruise in Minority Report, already having seen the precog verdict printed on that ball.

Conversely, when I'm the test audience for a little-seen video (a dead giveaway is it has almost no likes yet), I tend to be merciless in skipping ahead if it doesn't hold my attention after a few seconds.

This creates a ruthless rich-get-richer dynamic, but that's by design. Bytedance as a company has built its products around pitiless algorithms enforcing a high Gini coefficient economy of entertainment. It's a marketplace in which the supply side—the TikTok videos from creators—can be shown to an unlimited number of viewers. Much of the content is evergreen, so there is almost no end to the leverage TikTok can get off any single good video.

Imagine if YouTube's key metric was to show every good video in its entire catalog to every viewer that would enjoy it. If you view the TikTok mission that way, even if no one submitted another new video for the next year, its FYP algorithm would still have an almost infinite supply of short videos to show to hundreds of millions of users for that entire dry spell.

Because sounds become the genesis of particular memes, when you start watching a TikTok video and hear a familiar sound, you anticipate the moment of that sound when the punchline will happen. It's Pavlovian.

The kismet shoe transition, for example, causes you to anticipate the pleasure of that exact moment when the performer will go from looking plain to looking EXPENSIVE. There are only so many plots in Hollywood, but we go see genre films precisely for the story beats we know are coming.

On TikTok, sounds and memes are almost inseparable. The sound is the meme is the sound.

TikTok sounds are often the most pleasing snippets from pop songs, and listening to one catchy loop after another is like listening to a pop radio channel that doesn't play entire songs, only plays bass drops and choruses. The time between anticipation and payoff is so short that scrolling the feed can feel like pressing the button on some sonic IV drip over and over. Just inject it into my ears.

In Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace describes a film called Infinite Jest which is so entertaining people lose all will to do anything except watch it until they die. He had often written about the addictiveness of television and may have been extrapolating to the future, projecting the entertainment value of entertainment increasing until it surpassed some threshold where you'd lose all will to do anything except consume. In that way, he predicted binge watching.

But the earliest form of entertainment that conjured the addictive properties of his fictional film (referred to in the novel as "the Entertainment") was video games. I read stories about players who died after playing games for so long without eating and, recalling some game binge sessions from my youth, could imagine myself trapped in a similar dark loop.

TikTok is the second form of entertainment that brings DFW's fictional entertainment to mind. In hindsight, it seems obvious that a personalized feed of video, tailored to your tastes, would be the addictive end state of entertainment. And, considering the rise of social media and the smartphone, it would make sense that the videos might all be short, like pellets of rain, sliding comfortably into every spare pocket of time in our day, of which we have so many.

One of my favorite paragraphs of recent years was one describing the miracle that are Cheetos:

To get a better feel for their work, I called on Steven Witherly, a food scientist who wrote a fascinating guide for industry insiders titled, “Why Humans Like Junk Food.” I brought him two shopping bags filled with a variety of chips to taste. He zeroed right in on the Cheetos. “This,” Witherly said, “is one of the most marvelously constructed foods on the planet, in terms of pure pleasure.” He ticked off a dozen attributes of the Cheetos that make the brain say more. But the one he focused on most was the puff’s uncanny ability to melt in the mouth. “It’s called vanishing caloric density,” Witherly said. “If something melts down quickly, your brain thinks that there’s no calories in it . . . you can just keep eating it forever.”

TikTok is entertainment Cheetos. Each video requires so little cognitive exertion and reaches its climax so quickly that it feels like we could keep watching forever, each punch line scored to the most satisfying bass drop or stanza from every pop song. TikTok delivers dopamine hits with a metronomic rhythm, and as soon as we swipe up the previous one melts in our memory.

It's always been the case, but especially in this networked age, that every piece of entertainment is its own social network. The network effects of a story arise from shared consumption. The more people watch Star Wars, the more people I can talk to about particular scenes or compare costumes with at a convention. The more people that watch Game of Thrones, the more my Game of Thrones memes will land.

TikTok is personalized, yet through its algorithm it creates shared stories of real scale. Some of these shared stories occur on the creative side in duets and trims that connect creators to each other literally and metaphorically. The FYP algorithm also aggregates large communities of viewers for the hottest TikTok videos. It's not uncommon now for me to send a TikTok to a friend who's already seen it, or vice versa. Not always, but enough that the audience now assumes enough common knowledge to foster that sense of shared experience.

Despite having what must be a gazillion videos in its catalog, watch TikTok enough and you'll be able to refer to something like Sea Shanty TikTok and feel reasonably confident other TikTok addicts get the reference. In contrast, people regularly send me YouTube videos with like millions of views that I've never even heard of.

It is algorithms that may be tearing us apart. But maybe it's also algorithms that reassemble us, albeit in smaller unit sizes. 330M Americans feel like too large an optimal governance size if we're going to let social media algorithms just run amok, but I find some comfort sometimes when I find some TikTok that feels so catered to my tastes that it must be a micro-niche and then see it has millions of likes.

The term binge-watching typically refers to watching multiple episodes of a series in one sitting, but perhaps the act of watching dozens of TikTok videos in a row is the purest form of this type of entertainment gluttony.

Other types of social media like Instagram and Twitter are also series of really compact units of media. When I scroll Twitter or Instagram, I often feel like an elephant, standing there placidly, as various people toss individual packing peanuts at my forehead (let’s call these people the peanut gallery?).

TikTok videos are, for the most part, a bit longer. Their compressed narratives are still, nevertheless, complete, with some full story arc to traverse. In its rhythm, binge-watching TikTok reminds me of watching a standup comedy set, but instead of watching one comedian, I’m watching a whole series of them, each on stage just long enough to tell one joke. And if they bore me, I can press a button and, like a Looney Tunes cartoon, a cane whisks them off the stage and a new comedian pops out from the floor to take their place and start right into their joke.

Someone told me that if you watch TikTok for over an hour it posts a warning asking you to consider taking a break. I'm not sure if that's the case, but I'm glad I've never encountered it yet.

TikTok can only match you with videos it has, and for some people, there may not be enough relevant content in the TikTok catalog to sustain a feed. But that pool of videos has grown by an astonishing amount in a short amount of time.

I'm an easy mark for the sort of wry, sometimes savage humor of TikTok, especially when it skews almost post-modern in its awareness of its own form. It's both a community that constantly tries to legislate its own social norms of decency—any video of someone making fun of how they look using a supposed beauty filter will be flooded with comments like "You're a queen", the comments section being sort of a rolling floor vote on what the acceptable response is—and also a bloodbath of Gen Z violence. The kids will be alright, but that's in part because they're savage. Every generation learns it has to fend for itself.

During a pandemic when most of social media feels even more nakedly performative than usual, as we sit inside day after day for month after month, my occasional sessions on TikTok have been one of the only pastimes to reliably make me laugh, and it's not particularly close.

Twitter has reached a crest of fortune cookie thinkboi bait when it's not subsumed in petty high school lunchroom culture war fistfights. Seemingly every day, a playground brawl breaks out and we all form a circle to gawk, but at the back of our minds is always the threat that we'll be the next to be sucker-punched and forced to throw down. Outrage porn is exhausting and also not that fun?

When viewed from the eye of a global pandemic, Instagram feels like a horrifying Truman Show of idyllic capitalist showboating. Life must go on, influencers gotta influence, but I'm also not weeping any tears when people get chastised for renting private islands and posting photos of themselves partying during a pandemic.

Andrew Niccol, the screenwriter of The Truman Show, once said, "When you know there is a camera, there is no reality.” The most absurd but popular tag on visual social media is #nofilter, a hashtag that aspires to a pretense of truth when there is almost nothing on an app like Instagram that isn’t production-designed within an inch of its life.

TikTok, by virtue of its high bar to even produce a video that anyone will see (FYP algo is like "That's a no for me dawg" on almost every video), is upfront about what it is: a global talent show to entertain the masses. In a pandemic where much of the U.S. lives in eternal lockdown, TikTok is the 24/7 channel where the American Idle entertain each other from their bedrooms. I laughed, and then I laughed some more.