Reckless

Last Friday, I saw the second showing of the preview for a new Craig Lucas play, Reckless, at the Biltmore Theatre. Going in I knew nothing other than it starred Mary-Louise Parker, of whom I'm a big big fan, and that Craig Lucas had written Prelude to a Kiss which I'd never read or seen.

Last Friday, I saw the second showing of the preview for a new Craig Lucas play, Reckless, at the Biltmore Theatre. Going in I knew nothing other than it starred Mary-Louise Parker, of whom I'm a big big fan, and that Craig Lucas had written Prelude to a Kiss which I'd never read or seen.The play begins on Christmas Eve. Rachel (Mary-Louise Parker) is sitting in bed with her husband Tom as the snow falls outside on an idyllic suburban community. She gushes about how much she loves the holiday while her husband trembles in silence. He's not moved by her nostalgia; no, he's racked with guilt for having taken out a contract on the life of the mother of his two children. He spills the beans, ushers her out the window in her bathrobe just as the hitman enters their living room, and she's set off on a strange, almost absurdist journey.

She's picked up by a stranger named Lloyd at a gas station and invited to live with him and his deaf wife Pooty (Rosie Perez). Eventually Rachel gets a job at Lloyd's company, and a bizarre journey through financial scandal, game shows, and talk shows ensues.

The play feels not just surreal but imprecise. It's not a pure comedy, nor is it purely a drama or tragedy. The theme seems to center around a line Rachel asks Lloyd at one point, "Do you think you can truly ever really know somebody?" Clearly Rachel didn't know Tom, her own husband, well enough to understand why he'd take out a contract on her life. Nor, for that matter, does the audience. Lloyd and Pooty are not who they seem, nor is Trish, the assistant at Lloyd's company. Post 9/11, the bewilderment from being the object of hatred or harm from complete strangers resonates to some degree, but the play also contains some awkward attempts at comedy, especially a game show appearance in which near complete strangers Lloyd, Pooty, and Rachel prove to know more about each other than Rachel did about her own family. Is it luck, more proof that nobody really knows anything about each other?

The play ends with Rachel reuniting with her son in an unexpected way, and we're left wondering if she'll actually finally know someone. It's perhaps the most poignant moment of the play though it comes too late.

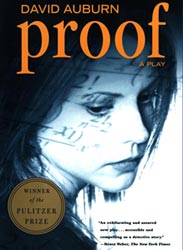

The part of Rachel casts Mary-Louise Parker as a wide-eyed naif, and perhaps my problem with the play is that she is so good as the smart and sassy woman, her large and penetrating eyes always seeming to see right through everyone. She's so self-assured on stage. Her origination of Catherine in David Auburn's Proof was definitive, and I wish she'd been tapped for that role on film (it went to Gwyneth Paltrow who also did that role on Broadway).

The part of Rachel casts Mary-Louise Parker as a wide-eyed naif, and perhaps my problem with the play is that she is so good as the smart and sassy woman, her large and penetrating eyes always seeming to see right through everyone. She's so self-assured on stage. Her origination of Catherine in David Auburn's Proof was definitive, and I wish she'd been tapped for that role on film (it went to Gwyneth Paltrow who also did that role on Broadway).Perhaps Parker's gaze is too penetrating. That may explain why both images in this post show her looking off to the side instead of directly at the viewer.