The John Wick Universe is Cancel Culture

“Si vis pacem para bellum”

translated

“If you want peace, prepare for war”

I hadn’t planned on seeing John Wick 3 - Parabellum, but out for a walk in Stockholm in May, I got caught in a sudden downpour without an umbrella. I was in Sweden for the first time thanks to an invitation from the Spotify product team and had decided to spend some of my downtime seeing the city. Sweden, by the way, is the country with the second highest unicorns per capita. Fascinating, and a topic for another day. I sprinted out of the rain and into the nearest building, which happened to be a movie theater. Checking Dark Sky on my phone, the rain didn’t look to let up for another hour or two, so I scanned the theater listings and found a film in English. John Wick 3: Parabellum it was.

Like many I enjoyed the first John Wick movie for its lean and elegant plot and balletic fight choreography. Keanu Reeves was inspired casting given his unfussy acting style. However, I thought the sequel was unnecessary. I wasn’t expecting much from yet another entry, the third, but I rarely regret spending two hours in a darkened theater. Watching an American film in the company of a Swedish audience also promised to be a form of cultural field work, and on that front, I felt fortunate the house was packed with locals.

John Wick 3 - Parabellum begins directly after the events of the previous film, and at first, all seemed familiar. But after having spent two films worth of time in this universe already, sometime midway through the third film, it dawned on me. The rules of this film franchise mapped with uncanny precision to something that everyone had been complaining about to me for years now: cancel culture.

With that, the films took on heightened resonance. Here I present my theory of John Wick Universe as an allegory of cancel culture.

[SPOILER ALERT: Here is where I must warn people who haven’t seen the films that I will reveal key plot points to the three Wick films below. I don’t feel like the charms of this film series lie in the plot details—what happens isn’t surprising in the least to even the most casual of action film fans—but I disagree with those who say spoiler culture has ruined film criticism. Instead I’m happy to let my readers choose their own acceptable quota of narrative novelty. If you prefer not to learn the plots of the John Wick films, stop reading here.]

Wick’s character motivation can be described thus: my name is John Wick. You stole my car. You killed my dog. Prepare to die.

Reeves plays Wick from cinema’s storied tradition of zen-like hit men, almost placid in their mastery of their craft, which, in his case, is the violent dispatch of other humans from the realm of the living. This is Alain Delon in Le Samourai, Robert De Niro in Heat, Jean Reno as Victor "The Cleaner" in La Femme Nikita. Less sexual than Bond, not quite as overtly cruel as Matz and Jacamon’s Killer. These hit men have a heart, but their highest order bit is the code by which they live. Whether personal or business, there's little difference, the job is killing.

And kill he does. In John Wick 3: Parabellum the signature choreography of death remains, a style which can only be described as baroque. Not John Wick for a single gunshot to the head when he can first maim with a few amuse bouche bullets to the torso and limbs. Why engage in a simple fist fight when one can hold a confrontation in a store filled with display cases lined with all manner of knives (in case of emergency, break glass with the skull of your combatant). Why simply perforate assailants with automatic weapons when they can be simultaneously be relieved of their genitals by an attack dog?

It wasn’t until Michael Bay’s terrible 6 Underground on Netflix that I saw a film with more cartoonish violence this year.

For some, this is entertainment enough. I’ll never hesitate to offer my opinions on any piece of entertainment, but I do not begrudge anyone their pleasures. Certainly, the crowd of Swedes who laughed and cheered at the escalating violence seemed more than entertained. For me, however, films are even more compelling when they speak to the world outside the edges of the screen. I'm nothing if not a sucker for subtext. What fascinated me about John Wick was how its absurdist universe acted as a wry commentary on cancel culture.

Do I think this subtext was intentional? Doubtful. Some filmmakers reward subtextual readings more than others. Still, the advantage of making a film with such a lean universe design is its semiotic flexibility.

John Wick’s real name, we learn, is Jardani Jovonovich, a Belarussian gypsy raised as an assassin. Wick is nicknamed Baba Yaga, the Boogeyman, for he is the master of assassination. Who are most gifted in using social media to sow chaos and division in the world, especially the United States, than the Russians? Having lost the Cold War they’ve come back in a more fluid and confounding form.

When the first film begins, Wick has left that world of violence behind for a peaceful domestic life with his wife Helen. But she dies from an illness, though not before leaving him a beagle to keep him company. The dog, along with Wick’s car, a 1969 Ford Mustang Mach 1, are recognizable to anyone as the two iconic totems of an American’s most sacred values.

When a group of Russian gangsters try to buy his car and Wick refuses, they break into his home, steal the car, and kill the dog. In Pulp Fiction, John Travolta complains to Eric Stoltz that some vandals keyed his car. Stoltz commiserates.

“They should be fuckin’ killed, man. No trial, no jury, straight to execution,” he says.

“What’s more chicken-shit than fuckin’ with a man’s automobile?” says Travolta. “Don’t fuck with another man’s vehicle.”

“You don’t do it,” agrees Stoltz.

In America, the car is the symbol of a man’s property and an expression of his individual freedom. The dog is the symbol of unconditional loyalty, man’s faithful companion as he rules over his domain.

The two totems of American sacred values

In a social media context, we can think of Wick’s dog and his car as representing those beliefs we hold sacred. When Wick loses his car and his dog, he is every one of us who sees one of the values we consider intrinsic to our personal identity impugned by some stranger on social media. That the perpetrators are Russian is nothing if not reminiscent of Russian agents sowing discord in American society in the run up to the 2016 Presidential election.

It turns out John used to work for the father of the leader of the gangsters who stole his car and killed his dog. That father, Viggo, upon learning what his son Iosef has done, calls Wick and begs him to let it go. Don’t feed the trolls, we are told time and again. But we, like Wick, cannot. His permanent sabbatical from assassination has come to an end.

As on social media, violence begets violence. Since Wick refuses to let the matter go, Viggo, to protect his son, sends a preemptive hit squad to assassinate Wick at his home. We never fight a single target on social media because the public broadcast nature of social media always rallies others to the cause. The first John Wick film proceeds from there as a series of attacks and counterattacks until Wick emerges, alive, bloodied, with a new dog, a pit bull he frees from an animal clinic. Viggo, Iosef, and what seems like a hundred or so henchmen are dead. The new dog symbolizes a brief moment of peace for Wick, just as we sometimes emerge from our skirmishes online feeling as if we have the moral high ground, our honor once again intact.

John Wick 2 begins with him retrieving his car from a chop shop owned by Viggo's brother, which requires Wick to kill not only Viggo’s brother but his fellow goons. The car takes serious damage in the firefight, much like the beating we take defending ourselves online, but Wick eventually emerges with his car and new dog and then returns home to bury his weapons cache. He thinks he is out of the game once again.

As anyone who has participated in culture wars knows, any victory is temporary and pyrrhic.

Out of the blue, Santino D’Antonio visits Wick at his home and calls in a marker, represented in the films by a medallion with a drop of blood from the debtor. Santino needs Wick to become an assassin again, just as various friends online call on us to take their side in various online battles.

John refuses. He wants out. The marker is the marker, though. If you won’t defend your values, then can you say you really have any? Santino reminds John of this in a not-so-subtle way: he blows up Wick’s house with a grenade launcher.

This brings us to The Continental, the unique hotel chain at the heart of the John Wick universe. Their Manhattan branch is run by Winston (Ian McShane) and staffed by the always courteous and professional concierge Charon (Lance Reddick). Now homeless, Wick retreats to the Continental for refuge. The entire Continental hotel chain lives under the aegis of the High Table, like one of the W Hotels in the former Starwood and now Marriott network.

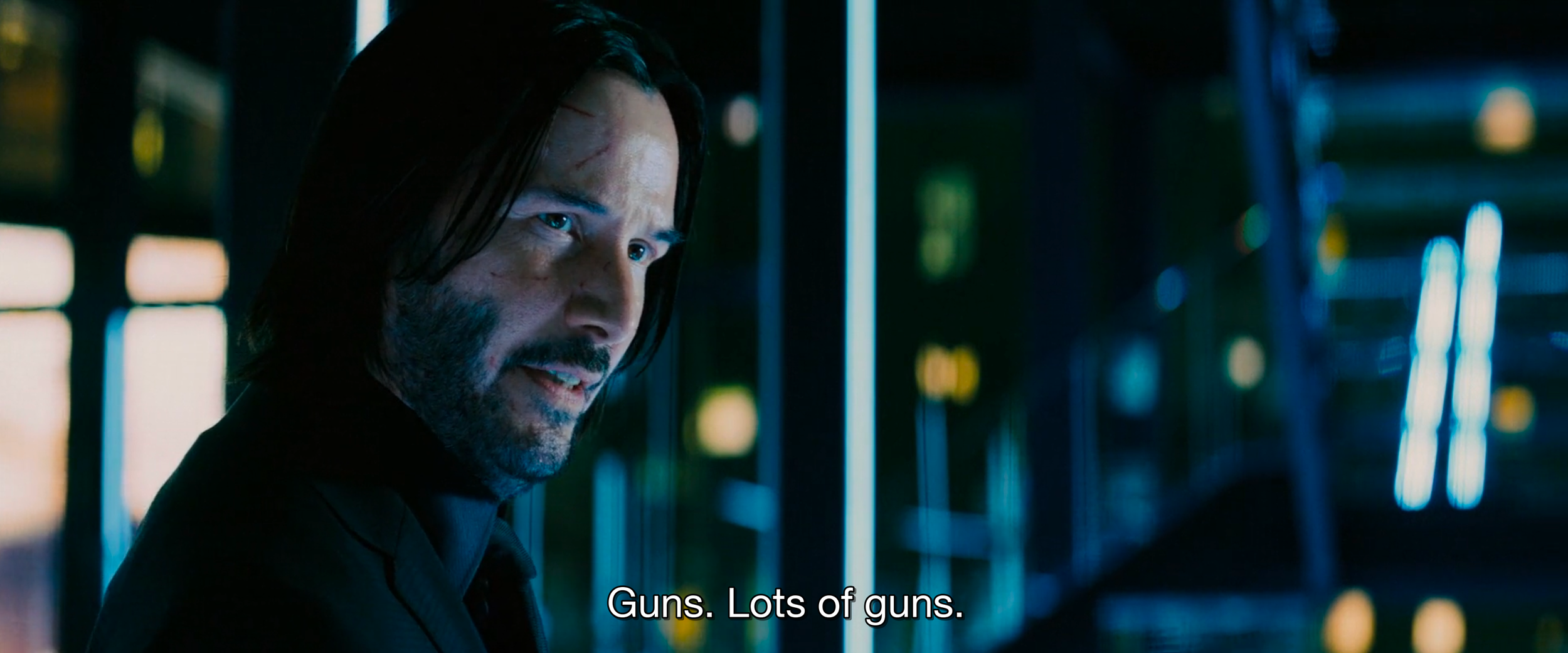

The Continental hotel chain stands in for our social media platforms. Like them, The Continental claims neutrality—no killing is allowed on Continental grounds—yet they happily arm assassins with all manners of weapons, like Twitter arming people with the quote tweet, the AK-47 of social media. They even employ a weapons sommelier.

The Continental sets all sorts of very specific policies that seem to be in conflict with each other; do they want civility or violence? Visitors to the Continental, like Wick, vacillate between wanting them to enforce rules and wondering who put them in charge in the first place. In other words, a mirror of the tension between users and the social networks that dominate the modern internet.

At any rate, Winston reminds Wick he must honor the marker from Santino, because them’s the rules. These markers are like metaphors for engagement, the debt we pay social networks for the privilege of their services and distribution. Social media platforms do not want violence on their grounds, yet they live through user engagement. The only way to not have any markers on your ledger is to never accrue a debt in the first place, but Wick was raised in the golden age of social networks, where it was near impossible to avoid being active on them. Bowing to the marker, Wick accedes to Santino’s request to assassinate his sister so Santino can assume her spot on the High Table council.

Wick carries out the mission, with great reluctance, only to have Santino turn around and put a $7 million contract on Wick for murdering his sister. This is akin to battling your enemies on social media platforms, creating the engagement that platforms thrive off of, only to have them turn around and lock your account for having done so. Many a person I know has complained about just such a betrayal. Pour one out for David Simon and his periodic bans on Twitter for eviscerating his opponents in a blaze of profanity.

Wick, as is his style, comes after Santino, who retreats to the safety of the Continental, where no violence is allowed. But Wick has been betrayed, and personal values now take precedence over the platform rules of The Continental. He pursues Santino onto hotel grounds and guns him down in front of Winston.

As penalty for conducting assassin business on Continental grounds, the High Table doubles the bounty on Wick to $14 million and broadcasts it globally. As the second film ends, Winston informs Wick of the bounty and gives him an hour head start to run. He sets off with his pit bull through Central Park as cell phones start ringing throughout the park. Wick has been true to his beliefs, as symbolized by the dog by his side, but the outrage mob is about to be set loose on him.

John Wick 3: Parabellum picks up from there. Wick is on the run through the rain of Manhattan, glancing at his watch as the seconds tick down to the global bounty becoming official.

In the Wick universe, official High Table business is processed through a central office by dozens of men and women dressed like old school phone switch operators, all of whom go about their jobs with an almost cheerful professionalism. Anyone who has ever received an impassive automatic reply from a social media customer service department after reporting some vicious attack can empathize with the almost comical formality of the Kafkaesque institution in the face of what feels like emotional terrorism.

That the bounty is put out by the High Table feels appropriate. It’s because of the algorithmic distribution of social media platforms that the asymmetric attack of the bloodthirsty mob achieves modern levels of scale and precision. The High Table seems elusive, at times arbitrary, just like the moderation policies of social networks. Winston at time seems friendly to John, yet he also stands by as the mob prepares to set upon Wick. Many users of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, and so on can relate to this love-hate relationship with those platforms.

As soon as Wick’s bounty goes global, seemingly every next person on the street comes sets upon him with the nearest weapon at hand. Anyone who has been attacked by an online mob, or even mildly harassed, is familiar with this uniquely modern sensation of being set upon by complete strangers. The Wick films give online mobs physical form. These random assassins are the Twitter eggs with usernames like pepe298174.

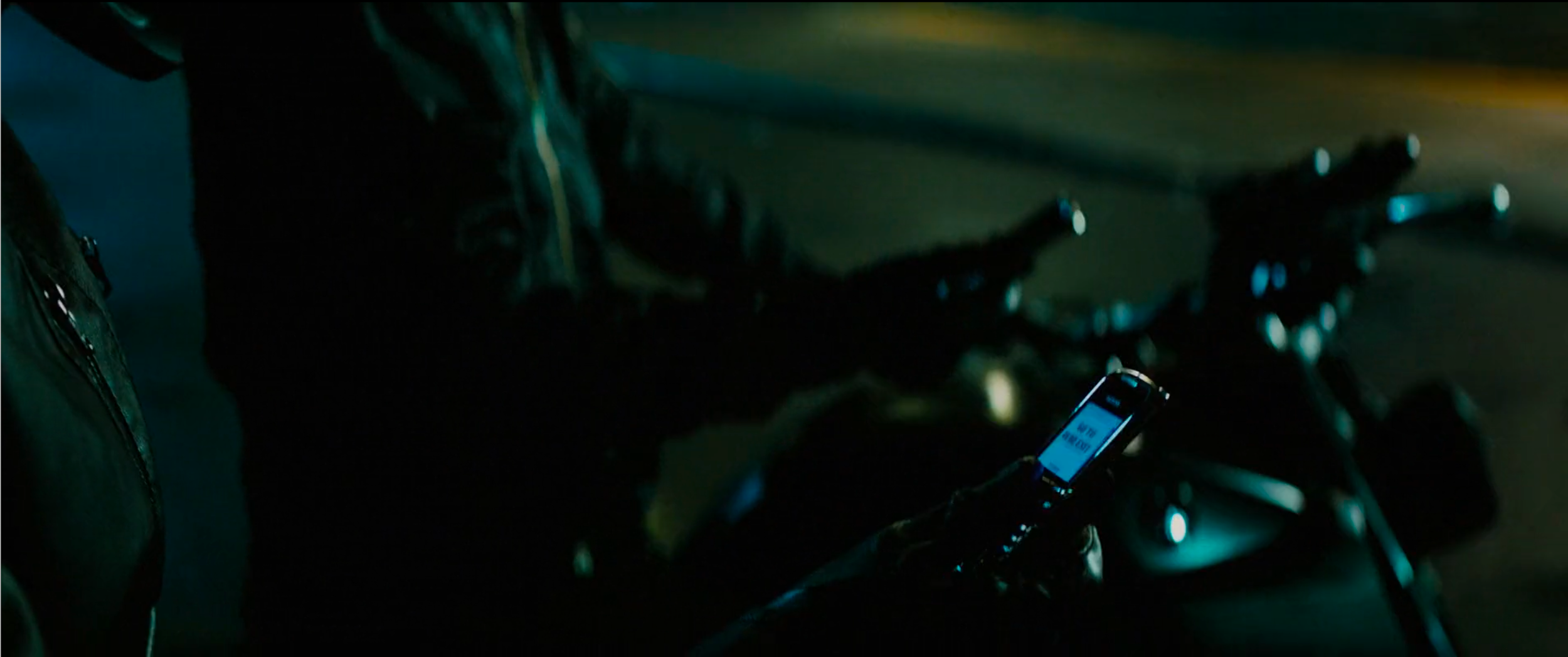

Even more perfect, strangers attack John Wick only after glancing at their phones and receiving word of the bounty. How do outrage mobs coalesce in the online world? From people staring at social media on their phones and locating the next target to be cancelled. The High Table’s bounty system, with its mobile notifications, is nothing less than a formalization of the mechanisms by which social networks enable cancel culture.

Wick dispatches one attacker after the other with every weapon at hand, whether axe or handgun or, in the first case, a hardcover book (when you absolutely, positively, have to snap a man’s neck using a book lodged in his jaw, a flimsy paperback or e-book just will not do).

I’ve talked to liberals who’ve been set upon by the alt-right. Women who’ve been attacked by gamers. Creatives who are set upon by outraged fans. Conservatives who feel swarmed by SJW’s. Everyone feels unjustly attacked by faceless mobs, everyone is aggrieved. Everyone feels they are standing up for their truth and their principles, like John Wick, while mindless strangers attack from all sides. John Wick is the avatar of the modern social media user, the "righteous man beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men."

Just before the bounty goes live, Wick stops by one of those doctors in the movies that caters to assassins and mobsters, the ones with fantastic service, always willing to provide bullet removal surgery on demand to walk-ins. Wick is bleeding from a shoulder wound inflicted by an overzealous assassin who tried to take John out before the bounty went official. Wick begs the doctor to patch him up, and he does, even pointing John to some medicine for the pain. But before Wick leaves, the doctor asks John to shoot him twice, to make it seem as if Wick coerced him into helping him. The doctor knows it is near impossible to stay neutral in the culture wars; if you’re not on one side you’re on the other. Ask Maggie Haberman.

John calls in a marker from a woman known as the Director (Anjelica Huston). She runs a ballet theater called the Ruska Roma that doubles as some sort of training ground for assassins; it’s implied that Wick learned his trade there. Once again, the blind loyalty to this marker system perpetuates a cycle of violence. Huston would rather not be involved, admonishing Wick, “You honor me by bringing death to my front door.”

Wick retorts in Russian, “I am a child of the Belarus. An orphan of your tribe. You are bound to help me.” He explicitly evokes the tribalism inherent in humans, the us vs. them impulse that social media amplifies. And then, in English, “You are bound, and I am owed.” The particular power of tribalism is the near impossibility of being neutral; to not pick any side is to be against everyone. The Director succumbs.

The face you make when your friend tags you into his or her online battle and you just want to watch YouTube

You were at my wedding Denise

As she walks him through the backstage training area of the theater, where other young assassins are in training, she says, “You know when my pupils first come here, they wish for one thing. A life free of suffering. I try to dissuade them from these childish notions but as you know, art is pain. Life is suffering.” As she says this, a ballerina pulls a toenail off. Social media is suffering, she is saying, but Wick is already in too deep.

She walks him past a bunch of men wrestling on the ground, future John Wicks in training.

She continues, “Somehow, you managed to get out. But here you are, back where you began. All of this, for what? For a dog?”

“It wasn’t just a dog,” he replies.

“The High Table wants your life. How can you fight the wind? How can you smash the mountains? How can you bury the ocean? How can you escape from the light? Of course you can go to the dark. But they’re in the dark, too.”

Huston is saying that the only way to avoid the darkness of social media is to avoid it, but, as he says, it wasn’t just a dog. She points him to the path out of the outrage cycle, nothing that it’s not a game you can win (How can you fight the wind? That is, there’s always another faceless troll.), but for Wick it’s a matter of honor.

She cashes in his marker, acceding to his request for safe passage to Casablanca.

Enter Taylor Mason. Err, sorry, the Adjudicator, played by Asia Kate Dillon. Employed by the High Table, she informs both Winston of the NY Continental and another character nicknamed the Bowery King (Laurence Fishburne) that they must abdicate their positions in seven days for having aided Wick in killing Santino (in John Wick 2).

If you’re a liberal, the Adjudicator is like the conservative government officials who’ve continually accused social media platforms of an anti-conservative bias, or the both-sides-ism of the media. If you’re a conservative, the Adjudicator is some metaphor for the liberal media, punishing social media platforms for anything other than absolute conformity to liberal narratives. Sometimes, when Twitter works itself into a rage at another NYTimes headline that isn’t tough enough on Trump, I think of the Adjudicator as the public, holding the newspaper to account for its failure to answer to the collective public High Table.

In Casablanca, Wick calls on another friend, Sofia (the ageless Halle Berry making a nice pair with the ageless Keanu), with whom he cashes in yet another marker. She, like The Director earlier, is not happy to be pulled into Wick’s personal battles. Sofia runs another branch of the Continental, so essentially Wick has fled one tech platform for another that feels obligated to shelter him. He may be excommunicado from the NY Continental, but he once came to Sofia’s aid, and she owes him.

“You do realize that I’m management now, right? I’m not service anymore, John, so I don’t go around shooting people in the head,” Sofia notes. She’s essentially a tech platform executive now, trying to avoid getting pulled into social media battles.

“Look, I made a deal when I agreed to run this hotel, and that deal said I had to follow the rules of the High Table,” she says. “If I make one mistake, one enemy, maybe somebody goes looking for my daughter.”

Sofia faces the risk of being doxxed and having some nutjobs go after her children. Years ago, John helped get Sofia’s daughter out of this dangerous world, and Sofia doesn’t know where she’s been shepherded. She doesn’t want to know because she knows it would put her daughter back in harm’s way.

“Because sometimes you have to kill what you love.” Sofia speaks for all those who keep their opinions to themselves online because the cost of being cancelled just isn’t worth the cost of being attacked by the mob. If she stays in the game, she will be pulled into vicious battles she wishes no part of. But in removing herself from social media, she loses out on some of the benefits they offer, like the chance to communicate with family and friends, in her case her daughter. Long ago she chose exit.

Meanwhile, in Manhattan, the Adjudicator visits a sushi stand and calls on the chef and his crew to help enforce penalties against Wick and all who aided him. The chef, named Zero, agrees. He is, like seemingly everyone in this world, an assassin, just as social media turned all of us into soldiers in the culture wars. Zero and his team seem willing to serve the High Table no matter what they demand; like most people, the lure of participating in an online mob is a form of universal human bloodlust. They can also stand in for platform moderators, trying to implement social network speech policies as best as they can.

First they visit the Director at the Ruska Roma. The Adjudicator confronts her over helping Wick despite his excommunication.

Huston defends herself. “He had a ticket.”

The Adjudicator will hear nothing of it. “But a ticket does not stand above the Table.”

Zero runs a blade through the Director's clasped hands as penalty.

Time and again, the John Wick mythology points to the seeming futility of the defending one’s values on social media. The price of picking a side is always to suffer egregious violence from the other side with seemingly no real winners, or to be have one's hands slapped by the platforms (or in this case, pierced with a sword).

Sofia takes Wick to meet her former boss Berrada, as he requests. Berrada runs a mint to manufacture the gold coins and markers that the assassin world operate on.

“Now this coin, of course, it does not represent monetary value. It represents the commerce of relationships, a social contract in which you agree to partake. Order and rules. You have broken the rules. The High Table has marked you for death.” Berrada describes both the way in which platforms turned our relationships into business arrangements (“commerce” and “contract”), the artificiality of their power—the order and rules are ones the platforms made up—and their power to deplatform or ban anyone who sign the user agreements.

Berrada asks Wick if he knows the etymology of the word assassin.

Berrada explains: “But others contend it comes from asasiyyun. Meaning ‘men who are faithful and who abide by their beliefs.’” The Wick Universe, populated with assassins murdering each other in an endless cycle of retribution, is a proxy for the users on social media who cannot stand by idly while others infringe upon their beliefs.

Wick asks Berrada how to find the Elder, the one who sits above the High Table. Berrada directs him to wander into the desert and hope that the Elder finds him.

Before Sofia and John can leave, however, Berrada demands something from Sofia in exchange for the favor. In face, he says he will keep one of Sofia’s two dogs, who accompany her everywhere. Again, the dog symbolizes a person’s most sacred values. On social media, we are always being forced by tribal battles to give up some of our values in order to stay out of harm’s way. This time, Sofia refuses.

Berrada shoots one of the dogs, but it is wearing a bulletproof vest (hey yo social media wars are vicious you can never be too cautious). Sofia huddles over her dog, then draws a handgun hidden under its vest.

John sees what she is doing and urges her, “No.”

But it’s too late. The thing about social media is that it takes just one savage troll to put us on tilt. Sofia shoots Berrada in the leg, and just like that she’s back in the culture wars.

After she and her dogs and John kill off Berrada’s nearby henchmen, she walks over to Berrada and considers shooting him in the head.

“Sofia, don’t,” urges John.

She shoots him in the knee instead. “He shot my dog.”

“I get it,” he replies, in the funniest line in the film. Anyone who has dealt with an online mob empathizes with friends when they fall under attack and go berserk in response.

When you know you should just mute and block and walk away, but damn, that SOB shot your dog

Sofia, John, and the dogs fight their way out of the facility, killing several dozen men along the way in the most elaborately violent ways possible, evoking the almost casual cruelty of online warfare. They steal a car and drive out to the desert where Sofia abandons John to his search for the Elder. He wanders through the desert in his suit, without any water, a user de-platformed.

Damn, I got booted off Twitter and Facebook

In Manhattan, the Adjudicator and her sushi chef moderators visit the Bowery King and make him pay penance for the seven bullets he gave John Wick with seven knife cuts to the chest.

In the desert, John collapses from exhaustion but is saved and brought to the Elder. John asks him for a chance to reverse his excommunication. The Elder offers him a deal: Wick must assassinate Winston, head of the Manhattan Continental hotel, and then serve the rest of his days under the High Table doing what he does best, assassinating people.

This is the Faustian bargain for being on these social media platforms. Drive engagement for them and play by their rules, whatever those are, or be excommunicated from them. John either stays an assassin, suffering a lifetime of fighting other people on social media, or he can remove himself from the platforms entirely.

“I will serve. I will be of service,” John says. To prove his fealty, he cuts off his wedding ring finger. We’ve all seen people lash back at trolls only to be banned themselves. The loss of Wick’s ring finger represents those values we compromise when playing by social media platform’s arbitrary moderation rules. Who among us hasn’t emerged from some online tussle feeling like we lost a finger ourselves, gave up some part of our humanity?

Oh boy, here come’s dat online mob!

Back in Manhattan, John has to fight his way past Zero and his henchmen to reach the Continental. Just as Zero is about to kill him, John puts his hand on the front steps of the Continental. Charon appears and tells Zero to lower his weapon. Again, the platform rules are the rules: no assassination on hotel grounds.

Inside, John and Zero sit in the lobby together and have a chat. Zero fanboys over having met the legendary John Wick, even while noting he’s more of a cat person. Nothing epitomizes the often arbitrary tribal battles online better than the fight between cat and dog people.

You like dogs? I guess we have to kill each other.

Many people have described the feeling of meeting someone in real life who they despise online and finding they get along better than they would’ve imagined. While it’s not always the case, the disembodied world of social media tends to amplify divisions. The John Wick films portray this multiple times; in every film, John has a moment where he and someone trying to assassinate him stop to share a cordial drink on Continental grounds before resuming their fight to the death a short while later.

If only we’d met offline rather than on Twitter, we might be friends!

Isn’t screaming at each other online productive?

Wick gets his meeting with Winston, who tells John that killing him will not honor his wife’s memory but simply return him to a state of subservience to the High Table. The Adjudicator joins them and asks if Winston will step down (reminiscent of the calls for CEOs like Zuckerberg and Dorsey to step down from their posts) and whether John will kill Winston. Both of them refuse, so the Adjudicator calls the home office and has the Manhattan branch of the Continental deconsecrated.

Blame me all you want for running this platform, but it’s just human nature John. I can’t fix that!

Of course, this now means that assassination can be carried out on hotel grounds, but also that John can now partake in hotel services, namely a visit to the gun sommelier.

“Let’s see, I’m going to need the ability to tag some mofos, and also to quote tweet their asses”

What ensues is what film critics love to refer to as an “orgy of violence,” (has there every been an “orgy of peace”?) though in this case, as the carnage is accompanied by Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, perhaps a symphony of violence is more fitting (again, why never a “concerto of violence”?). Charon, hotel staff, and John move about the hotel fighting off an army of High Table forces clad in such heavy armor that they seem impervious to bullets, almost like an army of online bots swarming their target.

The whole time, Winston hides in a secure vault, sipping a martini, emblematic, in many people's minds, of social media execs working from their cushy offices while users rip each other to shreds on their platforms.

Wow, Trump just declared war on Twitter!

Oh well!

John survives, as usual, dispatching everyone who comes after him. The Adjudicator calls Winston and asks for a parley on the rooftop of the Continental, where John eventually arrives. Winston asks the Adjudicator for forgiveness and offers his ongoing loyalty to the High Table. The Adjudicator agrees to reconsecrate the Continental and restore Winston as manager, but then she turns to John and asks Winston what is to be done of the titular assassin. Winston replies by shooting Wick repeatedly in the chest and knocking him off the roof of the Continental, where he falls several stories to the alley below, bouncing off a few fire escape railings and awnings in the process. Ah, those platforms, they're always liable to turn on you.

Wick is not dead, as you’d expect. The Adjudicator, on the way out of the hotel, peeks in the alley, where Wick’s body is nowhere to be found. He has, we discover, been brought to the Bowery King, now maimed by all those knife wounds ordered by the Adjudicator.

What outlook does John Wick offer us on the state of the online discourse moving forward? Is there any hope for relief? The end of the film isn’t optimistic.

Laurence Fishburne says to Wick, lying there in a bloody heap on the ground: “So, let me ask you John, how do you feel? Because I am really pissed off. You pissed, John? Hmm? Are you?”

John Wick strains to lift his bloodied head off the ground to look Fishburne in the eyes. “Yeah.”